We have always spoken of mental art, of behavioural art, from which performance comes, but we have always continued looking for the “sex of angels”. We all know, through simple reason, without requiring too high a level of wisdom, that creativity is not born under the wing of the social elite, but elsewhere; if, however, reality leads us to the opposite, this means that we have fallen for the deception and have therefore broken the rules of bridge, and are therefore no longer playing bridge. The “important” artists always remain those of the given class and never the others, the outside class, that appear not to exist. But is it really like that?

During the Yugoslavian civil war, 1991/1994, I carried out in Belgrade, in Novi Sad, in Hungary (with Otto Tolnai) and at the Academy of Arts in Düsseldorf (with Clause Rinke) various performances with that verbalized this theme. What’s more, I did various interviews, for newspapers, magazines and TV, where I spoke out against the war, associating the art of the system with the various “new philosophers” of the western left, the so called “differentialists”, committed to justifying the war and asymmetrism. I saw a class of media intelligentsia working as mercenaries. I wrote various articles for specialized newspapers where, amongst other things, I wrote about Situationism (“the revolution of modern art and the modern art of revolution”), trying to remind people of that which seemed to me most important, driven by the forgetfulness, namely forgetfulness itself.

It was badly taken by the nationalist right, generously backed by the differentialist left and the CIA. What confusion!? People died in the midst of confusion, like hens, and, in fact, these are our times; times of loss and fear. In short, my position is that of trying to survive. I am not one of those people who by today has made themselves a fortune, and I am proud of this.

The Fluxus movement are my friends by nature, particularly Boris Nieslony and the former Büro Berlin group. Imagine: in 1987 I found myself in Dubrovnik, in artistic retreat, and one day I found that Boris Nieslony had come to look for me, which was a real surprise. Who knows how he managed to find me? My address in Dubrovnik did not exist, yet he found me; he stayed for only a few hours, enough to tell me about the exhibition of “Büro Berlin”, in which he wished me to take part in a performance together with him, two performances as one. We ate something and then he left, everything in a few hours. This is how Fluxus artists are.

It was the summer, and in the autumn I arrived in Berlin, as we had agreed. Everyone from Fluxus International was there. Thus closing a chapter of the Berlin group. Fluxus, more than anything, was a way of behaving, but not necessarily. I think that the work of art and the operation of art, and the things that are found in the middle, according to the mathematical principle of “linear inference”, are subsequently explained by each other. In short, Fluxus cannot be explained. One can, if they really want, give a liberal interpretation, as I do in this moment, so as to not be impolite to someone asking the question, but afterwards I add that I may be mistaken…

As for the rest of the question, I start by saying that there are some artists that suffer absurd injustices (speaking of those who don’t belong), because they do not pay attention and don’t want to pay attention to the rules of artistic society and the interests of the market.

The Gap gallery was the gallery that operated outside of this, trying to give space to “self- excluded” artists, whose work by nature was not codified by their ideological concept, with the exception of Paik and Vostell, seeing as they are mentioned in the question, who were present in both camps. Much depends on the strategy of an artist’s work, it depends on the methods, the expressive manner, the artist’s character, and perhaps even the friendliness and charm of the artist’s persona. There is volume in which the activities of the Gap gallery from 1972 to 1975 are documented, but I would rather say a few words about Giovanni Fileccia, the founder and director of Gap.

Gianni was a political scientist with a background in TV and cinema. Then, at the end of the Sixties, he decided to delve into the ideas of the protests of 1968, which had barely been covered in cinema, and so he had the idea of finding the artists, and opened a gallery in Via Monserrato that was completely different to the galleries of the time. I met with Gianni in Milan in 1972, then we saw each other again in Bologna, where I was living at the time, and he suggested that I moved to Rome. He gave me a place to stay near the gallery and in this way I entered into Gap’s activities in 1973. There was a group of artists (I won’t mention names) around the idea of “art, life and politics” as a bringing together of ideas, things and facts, in a permanent and open debate. It can be said that it was the only Italian, and obviously also international, gallery of Fluxus, even if there were no statements in this regard.

The space was almost always empty, there was a large table at the centre with writing paper, and in this way anyone who came inside had this opportunity. They could leave a message, written or drawn, as it was wished, and in this way “material” was created that was then communicated with the world in a cyclostyle way; or, given that Gap had an anonymous billboard at Porta Portese, where giant posters were shown, one could photograph the chosen message, blow it up and hang it on the board. I did it too.

** Part of the interview with Vania Granata, November 2003.

Ilija Soskic, Hohenzollern, performance per video super 8,12’, 1976, Video e performance realizzati presso il Palazzo Reale Hohenzollern, Tübingen per la Galleria Dacic. Foto a col. di Zivojin Dacic.

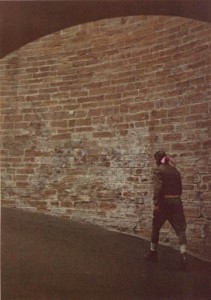

Ilija Soskic, Latte-Seta. Energia massima tempo minimo, performance-azione in 4 atti (sparo nel muro), 1975, Galleria L’attico, Roma, nell’ambito della mostra 24 ore su 24, Foto Lionello Fabbri.