If I could have stopped the war with a painting,

I would have done that;

but I’m not a good painter

JON HENDRICKS

In the twenty years at the turn of the 60s and 70s – like never before – art escaped what the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) could had defined ‘its paradoxical death’.

It was an era of great international changes and socio-political tensions ascribable to various causes; among others: the tightening of relations between NATO countries and the Communist countries; the out-breaking of war hotbeds in Asia (like the Vietnam’s war); the global industrial restructuring and the economic boom that didn’t produce an equitable distribution of wealth.

In art scene, the Situationist International’s experience, the Duchamp-inspired American neo-avant-garde and the early happenings of Allan Kaprow paved the way for propagating radical attitudes that seemed to willing to fulfill the Hegel’s prophecy on the death of art. The overcoming of the concept of ‘representation’ as the ultimate goal of artistic practice contributed to spreading the idea that art should had not reflect but identify itself with the real and its mechanisms. That is how the breaking of boundaries between art and life was finally produced. While these margins were progressively consumed, the process of dematerialization and the – partial or total – disappearing of the art-work – which had begun with the avant-garde in the early years of the twentieth century – came to its full maturity. Under the impetus of the real, artists increasingly began to practice anti-theatrical actions, which burst in everyday life with a provocative force, amplifying the lack of interest in the work-object and giving birth to a total dismantling of aesthetic codes and boundaries between mediums. The artistic urgency of a break into the everyday life went hand in hand with the phenomenon that – in his essay The precession of simulacra – Baudrillard described as the ‘agony of the real’, which means the gradual disappearance of the reality behind its multiple simulations. Following the thought of the French philosopher, the paradoxical condition which occurred in those years, was that the art ceased to ‘represent’ in order to ‘identify’ with a real that in post-modern society had become a hyper-real, or an incubator appearances (simulacra). More than that, in some way, the vocation to processual attitude, taken at the flood, saw the art devote itself to a self-destruction in the name of the preservation of what was considered its own raison d’etre, the exaltation of a concept, instead of the production of objects. This attitude could be better understood by the example of the ethnological paradox described – once again – by Baudrillard. In the early 70s, the Philippine government, in accordance with anthropologists, had decided to not involve the tribe of the Tasaday – that was remained isolated for centuries in the heart of the Mindanao island’s jungle until those days – in a civilizing process that would definitively extinct their culture. The French philosopher cited the example as a paradoxical suicide. In fact, a science that in order to preserve the existence of its object deliberately decides to give up his raison d’etre – that is the direct observation and study – is emptied of its meaning and condemned to death.

In a similar way, the artists which were active in the 60s and 70s – the alleged ‘killers’ of art, acting alone or in organized groups, among which the most famous was probably Fluxus, but we can remember the Japanese Neo-Dadaism Organizer, the Aktual from Prague, the Actionists of Vienna, the Croats Gorgona and many others all over the planet – seemed to want to act out the End of the Art to ensure its survival.

In that radical climate, under the impetus of the protest movements which were spreading in intellectual circles around the world, those artistic practices – which are remained marginal until a few years ago, but today, more alive than ever, fall within the definition of Art Activism – originated. An art that is no longer ‘representation’ but ‘demonstration’, in the specific sense of an express dissent, or to use the words of the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, (an art that is) end of the representation, if that means show something in its absence, but still representation, if that means manifestation, present the un-presentable, expose in the sense of doing an ‘exposé’ and express some remonstrance.

Among the art collectives referable to this attitude, two in particular have held my attention because of the similarities between their modus operandi and their objectives, despite the geographical distance and the different historical and social context in which they worked: the Tokyo-based Hi Red Center and the New York based Guerilla Art Action Group. Born at a distance of several years, the two groups had not direct exchanges. Jon Hendricks – one of the founder member of GAAG – knew about the existence of the Tokyo-based group, but since the documentation of their activities had not yet been translated into English, their practice was virtually inaccessible to Japanese non-speaking people. However, it might be said that until a few years ago, the work of GAAG – even though it was well documented in English – was not very known nether, outside of New York art scene.

The radical approach, their lash out against the establishment, their outsider nature and their artistic practice focused on ephemeral – often unannounced and almost always non-authorized – actions, which were turned to reveal the political dynamics and power games with which the art world and society are used to deal, had make difficult their diffusion and also a historicizing process. In the light of more and more globally widespread Art Activism practices, it is now possible to analyze the work of these two collectives under a new perspective. It is finally conceivable to contextualize their artistic practice into a global attitude that it is defining itself more and more clearly since the 90s, and to fully understand the pioneering value of their research.

In recent years, a renewed interest in the postwar Japanese art has been demonstrated by some major international institutions, which have promoted exhibitions aimed to shedding light on those years of great cultural ferment for the Asiatic archipelago. In particular, two major exhibitions – Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde showcased by the Museum of Modern Art of New York between November 2012 and February 2013; and even before Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan, 1950-1970hold at the Getty Center in Los Angeles between March and June 2010 – have focused on revolutionary instances which aimed the Japanese art scene since the end of the great conflict. As the previous decade, the 60s were still a transition period for Japan. Despite the considerable progress of the economy, popular discontent and social unrest continued to increase. The population was mainly afflicted by problems related to industrial system restructuring and structural changes which had caused serious environmental damage, exaggerated rise in prices and a massive depopulation of the countryside in the face of an enormous overpopulation of cities. Moreover, at an international level, despite the beginning of a relaxation policy had led to a normalization of diplomatic relations with the neighboring nations and with the countries damaged during World War, the intolerance towards of American foreign policy, exacerbated by outbreak of war in Vietnam, grew from year to year and was the primary cause of numerous protest by extremist wings of the population. In 1968, some agitators attacked the American Embassy, the Diet Building and the Ministry of Defense; plus groups of armed students stormed the Shinjuku station, forcing the government to declare martial law. In 1969, the outbreak of the protests concentrated in university circles. After occupying the Tokyo Daigaku, the students took to the streets to demonstrate against the former Head of Cabinet Eisaku Sato and the once again renewed Japanese-American Security Treaty, which basically kept to authorize an American military presence in the Asiatic archipelago.

The urgency of revolt is fully reflected in the art scene of those years. Thanks to the improvement of communications and the newfound mobility of artists, trends and international movements could more easily get Japan that, in those years, began to develop specific languages characterized by radical artistic expressions and practices. The art critic Tōno Yoshiaki (1930-2005) coined the definition Post Hiroshima Generation to indicate the members of the collective Neo Dadaism Organizers, created in 1960 by Ushio Shinohara (Tokyo, 1932) which are remembered for their provocative performances characterized by a refusal of social consensus. The definition of Tōno was referring to a whole generation of artists who had spent their childhood in the rubble of the American bombing. The destruction, the ruins, the sense of the material dissolution and then the sudden sinking of an entire system of values that had inspired previous generations deeply contributed to imprint the formative years of these artists, inevitably influencing their choices of future artistic expression.

The Hi Red Center – a group founded, in 1963, by Gempei Akasegawa (Yokohama, 1937) along with Jiro Takamatsu (Tokyo, 1936-1998) and Natsuyuki Nakanishi (Tokyo, 1935) – was born by this radical climate. The name of the collective was created by translating into English and putting together the initial characters of the last name of the three components: ‘Hi’ (short for high) – in Japanese ‘taka’ 高, Takamatsu 高 松 – ‘Red’ – in Japanese ‘aka’ for Akasegawa 赤 赤 瀬 川 – ‘Center’ – in Japanese ‘naka’ for Nakanishi 中 中西. In its short period of life – ufficially the group was active only one year – the Hi Red Center gave rise to various happenings whose goal, as Baudrillard would had said, had seemed to be the unveil of falsity of the real. Most of these actions, which could take place into exhibition spaces, such as the gallery Naika in Tokyo, or on the streets of the city, generally were not announced and did not ask for a particular audience, sometimes they just didn’t address to anyone, subverting in this way the performer-spectator relationship. Speaking about them, the art historian Reiko Tomi described their practice as an evolution from the Anti-Art (in Japanese Han Geijutsu – 反 芸 術) to a Non-Art (Hi Geijutsu – 非 芸 術) and in fact the Hi Red Center’s happenings can be considered as a set of ironic attacks on the basic conception of art.

During the 15th edition of the Yomiuri Independent – an artistic event promoted by the homonymous Japanese newspaper that encouraged neo-avant-garde and experimental researches from 1949 to 1964 – Takamatsu took a rope that ran through the exhibition hall and the garden outside until to Ueno Station. Akasegawa wrapped chair, electric fan, radio and carpet with reproductions of 1000 yen bills and Nakanishi began to stick on himself a lot of cloth pins until his entire face was recovered, then he ask the audience to do the same and he also invited people to attached pins on burnt canvas and undergarments hanging on the walls or piled on the floor. Very shortly after, the three artists decided to formed the collective. The Hi Red Center’s artistic practice was very close to that of Fluxus, and in fact, favored by United States-based Japanese artists, as Shigeko Kubota, Ay-O, Mieko Shiomi, Yoko Ono, Kuniyoshi Akiyama, there were recurring exchanges and collaborations between the two groups. For exemple, in 1964, Shigeko Kubota introduced the work of Hi Red Center to George Maciunas and Bundle of Events – a brochure mapping all the actions which the Japanese group carried out in Tokyo – was inserted into the Fluxus collection I box. A year before, Yoko Ono and Nam Jun Paik attended the happenings Shelter Planat the Imperial Hotel in Hibiya, in which the spectators were invited to stand in front of a white wall, in order to be measured and photographed by both sides, front and back.

Their actions seemed to remember those of the members of an other well known Japanese artistic collective, Gutai, but the goal of Hi Red Center was completely different. The Akasegawa’s group was not interested in painting or – in a broader sense – to the creation of concrete works that could had be sold could had be regarded as a part of the economic dynamics which were object of their criticism. Their intent was rather to undermine the system of art – but also the society – from the inside, through interventions that showed its futility and stupidity.

In one of their first happening, they invited a large number of people at a banquet in Kunitachi, a suburb of Tokyo, to commemorate the defeat of Japan in World War II. People paid a ticket but when entered the room realized they were being teased. In fact, there was no food for them but only for the artists. The public was astonished, offended and irritated, because was not authorized to really participate in the party, but just watch Takamatsu, Akasegawa and Nakanishi while they ate, drank, danced and even when they started to brush their teeth. The condition of the spectator was somewhat similar to that experienced by the Japanese people who believed in the promises of the imperialist government and got involved in a long war without any real benefits.

In Cleaning Event (Campaign to Promote Cleaness and order in the Metropolitan Area), executed during the Tokyo Olympic Games in October 1964, the Hi Red Center – wearing doctors white coat and surgical masks – swap Ginza’s sidewalks and roads, flooding the streets with flyers that bore the phrase ‘Be clean’. The purpose of their action was ridiculed the government’s campaign that was started several months earlier in preparation for the Olympic Game. The happening was not announced and the artists did their best for make it appear like an official initiative, insomuch as received the thanks of a policeman, persuaded of their seriousness.

One of the most interesting consequences of Hi Red Center’s artistic activity was the lawsuit in which its founder was involved. In 1964, Akasegawa printed a series of 1000 yen bills that he used for cover paintings, panels and different objects.

The fakes were extremely accurate and similar to the originals in order to thin the boundary between fiction and reality, as he explained a little while after in a text published in the journal of the Criminal League, that was a group of students from Waseda University already known to the authorities for their radical ideas. Because of this work Akasegawa was involved in a trial for fraud and counterfeiting, which ended only in 1974. During those years, for supporting the cause of the artist, a special committee was set up: 1,000 Yen Note Incident Discussion Group. The members of the committee were critics, art historians and artists, which argued the defense of Akasegawa, presented art works and pieces as exculpatory evidences, using their position as defense witnesses for developing debates and discussions around artistic issues such as the relationship between fiction and reality, freedom of expression and mechanisms of power.

The evidences presented in the trial were treated like art documentation as all the lawsuit could had been seen like a long performative project. The end of the story is even crazier than its starts. Pursued by the government because, according to the Japanese law, only sovereign states are allowed to issue currency, the artist proclaimed himself an independent nation, consisting of a single person: Akasegawa Gempei Capitalistic Republic. Only after this absurd declaration the Supreme Court acquitted him.

The Hi Red Center officially were active just a year (from 1963 to 1964) in fact their group broke up in concomitance with the beginning of the Akasegawa’s trial that was a direct consequence of the artistic research carried out by the group.

The trouble with the law and the habit of resorting to actions at the limit of legality is one of the points of connection between the Hi Red Center and members of the New York collective Guerilla Art Action Group. Founded in New York in 1969 by Jon Hendricks (Evanston, USA, 1939) and Jean Toche (Bruges, Belgium, 1932) in a climate of growing hostility to the Nixon presidency and its foreign policy, the group remained active until 1976. As the name suggests, the practice of this duo – to which were occasionally added Poppy Johnson, Joanne Stamerra and Virginia Toche – was based on a series of actions, often unannounced and never officially authorized, which took place in street, in public offices or in museums. Like the Hi Red Center also Hendricks and Toche sought to attack the system of art and contemporary society trough operations contesting its distorted behaviors with an attitude not devoid of humor. Even more radical than the Japanese collective, GAAG demonstrated a willingness to play with the paradox and highlighting the ironic tragedy of the fact that they denounced. The interventions of Hendricks and Toche were real jammer devices of social conventions and its dynamics. Through the practice of raid in daily life – continually perverting the boundaries between creative intent and political – their works can also be read as a tool of unveiling mechanisms of the real’s fictions.

In their manifesto, completed on October the 30, 1969, GAAG did three requests to the Museum of Modern Art of New York. The first was that it had to be proceed to the sale of works from his collection for a total of $ 1 million and that the proceeds were to be donated to the poor of all ethnicities within of the country. “We as artists feel that at this time of social crisis there is no better use for art than to have it serve an urgent social need”. They said in their manifesto. In essence, GAAG asked the museum a strong symbolic act, which would show the will to really closer art to the people and their needs. “The donation is a form of reparation to the poor, for art has always served an elite, and therefore has been part of the oppression of the poor by that elite”.

The second request made by GAAG concerned the structure of the museum and demanded abolition of the hierarchy of roles, in favor of a free access to its management by anyone, so that institutions were no longer tools in the hands of a elite, but a testimony of the will of the people. Finally, the last point demanded by Hendricks and Toche was that the museum remain closed in protest until the Vietnam War was over.

The day after the drafting of the manifesto, GAAG planned his first happening, which took place at the MOMA, in the presence of many members of New York’s artistic community. After had paid their entrance, Hendricks and Toche went to the exhibition gallery on the third floor, waited until the museum guards had left the room and lift the Kasimir Malevich’s painting White on White from the wall and gently placed it to the ground. After that, in front of a number of witness, they hung in the place of the painting a copy of their manifesto, asking to be received by a representative of the museum. After a while, the director of exhibitions, Wilder Green, arrived. The artists handed their manifesto to him and he said that the requests had to be presented to the museum Board of Trustees.

A few days later, GAAG returned once again to the MOMA to perform another intervention, A call for the immediate resignation of all the Rockefellers from the board of trustees of the Museum of Modern Art, also known as Bloodbath. Hendricks and Toche with Poppy Johnson and Silvianna entered the lobby of the museum and began to push each other, shouting and tear off what they were wearing. Then while a crowd of onlookers gathered around them and museum guards remained undecided on what to do, they did burst blood bags, which they had brought hidden under their clothes, and finally slumped in the puddle that had flooded the floor.

This time, their request involved one of the richest families in the country, the Rockefellers, the main financial supporters of the museum. According GAAG, the economic interests of the Rockfellers in the industry of war were incompatible with the mission of the institution. Hendricks and Toche accused the MOMA to destroy the integrity of the art by putting it at the service of people who used it as a way of glorify themself.

In the following months, GAAG’s interventions involved other important art institutions of New York. In the hall of the Whitney Museum – that was accused by the artists of lack of solidarity with the thousands of victims of American war policy on the other side of the world – after having scattered heaps of red pigments on the floor, the group began to kick up a fuss about the dirt of the venue. “We have to clean this place, it is dirty from the war. Hendricks and Johnson clamed kneeling on the ground: “What a mess, we have got to clean up”.

At the Metropolitan, during the exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, the first exhibition of contemporary art that was presented in the museum, GAAG staged an action that was addressed to the curator Henry Geldzahler (1935-1994) and aimed to blame the condition of the artists which were considered like mere puppets in the hands of the cultural establishment. They also want to denounce the enslavement of the museum to large enterprises, referring in particular to the donation of $ 150,000 made by the Xeros Corporation to support the event. Jon Hendricks, in the role of the curator, wove great voices in the praises of the great artist Jean Toche, who huddled inside a trunk, ate and drank everything his partner gave to him, it did not matter if it was milk or caviar sandwiches. The food and the drinks were falling soiled him. The request to meet Geldzahler was rejected and the performance ended without action on the part of the police.

Alongside the happenings, GAAG produced radio broadcasts and manifestos, poems and letters addressed to various important people including the President Nixon and the curator of the fifth edition of Documenta, Harald Szeemann.

Their activities continued, faithful to itself, for years, refusing to imprinting their stylistic aesthetic onto reality, dealing with day-to-day realities and with urgent issues, not personalities. The group was disbanded on December 13 in 1976 with a brief statement, signed by Hendricks and Toche, announcing: The Guerrilla Art Action Group is dead. Foul play is not suspected, police said yesterday, that seemed to be a lapidary and essential death certificate or the epitaph of an era.

Torna alla versione italiana / Italian translation

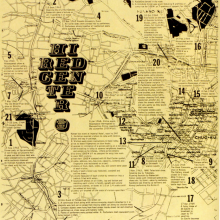

HI RED CENTER. “Bundle of Events”. Map documenting the performance of the group in Tokyo. Edited by Shigeko Kubota e George Maciunas, 1965 (Fluxus Edition, New York). Credits Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

HI RED CENTER. “Bundle of Events”. Map documenting the performance of the group in Tokyo. Edited by Shigeko Kubota e George Maciunas, 1965 (Fluxus Edition, New York). Credits Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

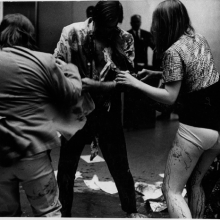

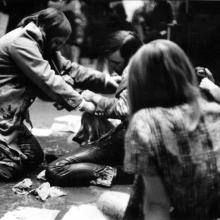

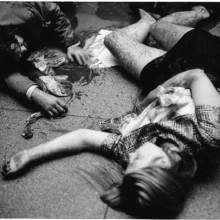

GAAG “The Bloodbath” performance al Moma di New York. Photo credits Hui Kwa Kwong

GAAG “The Bloodbath” performance al Moma di New York. Photo credits Hui Kwa Kwong

GAAG “The Bloodbath” performance al Moma di New York. Photo credits Hui Kwa Kwong