[1] See Boris Groys, “Moskovskii romanticheskii kontseptualizm,” A-YA 1 (1979): 3-11; 52; also see V. Patsiukov, “Project-Myth-Concept,” A-YA 2 (1980):7-9.

[2] “Я же не произвожу текст, я произвожу художественное поведение” (“I don’t produce text, I produce artistic behaviour”). Per-Arne Bodin, The poet Dmitry Prigov before and after the fall of the Soviet Union, text posted on October 10th 2011 in http://www.postcolonial-europe.eu/sv/studies/97-the-poet-dmitry-prigov-before-and-after-the-fall-of-the-soviet-union-per-arne-bodin-stockholm-university.html, p.4. Per-Arne Bodin takes the quotation from “Dmitrij Aleksandrovič Prigov”, N.Ž.M.D.: Literaturnoe kafe v Internete, http://www.tema.ru/rrr/litcafe/prigov/, 10-09-2010.

[3] Ekaterina Degot, A Play on Stage, in: D.A. Prigov, Citizens! Please Mind Yourselves!, Moscow, Moscow Museum of Modern Art Publishing Program, exhibition catalogue, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, May 13th-15th June 2008: 14.

[4] See Margarita Masterkova (Tupitsyn), “Performances in Moscow,” A-YA 4 (1982 ):6-11

[5] Ekaterina Degot, op. cit., 51.

[6] Ksenya Gurshtein,The Eloquent Spaces of Silence: D.A. Prigov’s Visual Art, lecture of 22nd February 2013 (typewritten text, p. 10) at the Conference Utopia III: Contemporary Russian Art and the Ruins of Utopia, London, Courtauld Institute, 22nd-23rd February 2013. She quotes Prigov’s introduction to his own Tri grammatici of 2003.

[7] Philip Metres, The End(s) of Russian Poetry: An Interview with Dmitry Prigov, in: http://behindthelinespoetry.blogspot.it/2007/07/ends-of-russian-poetry-interview-with.html

[8] Andrei Monastyrsky, ad vocem: THE NEW SINCERITY [Novaia iskrennosti], in the Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism: An Adaptation of Andrei Monastyrsky’s «Slovar´ terminov Moskovskoj, kontseptual´noi shkoly», edited by Octavian Eșanu, http://www.conceptualism-moscow.org/page?id=198&lang=en

[9] Per-Arne Bodin, op.cit., 1.

[10] Cf. http://prigov.ru/: Пригов Дмитрий Александрович, Вознесение (introductory text by Dmitri Prigov). Cf. also note 36.

[11] Ylena Fedotova “madman”, 8th July 2011, http://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/yelena-fedotova/dmitri-prigov

[12] Cf. Sergey Shapoval, (2012), op. cit., 90.

[13] Cf. Sergey Shapoval (2012), op. cit., 91 and also Helena Fedotova, op. cit.

[14] Per-Arne Bodin, op.cit., 8.

[15] Per-Arne Bodin, op. cit. writes about this work «Svet vo t´me svetit» [The light shines in the darkness].

[16] Cf. the Interview with Philip Metres, op. cit. (1996-2007).

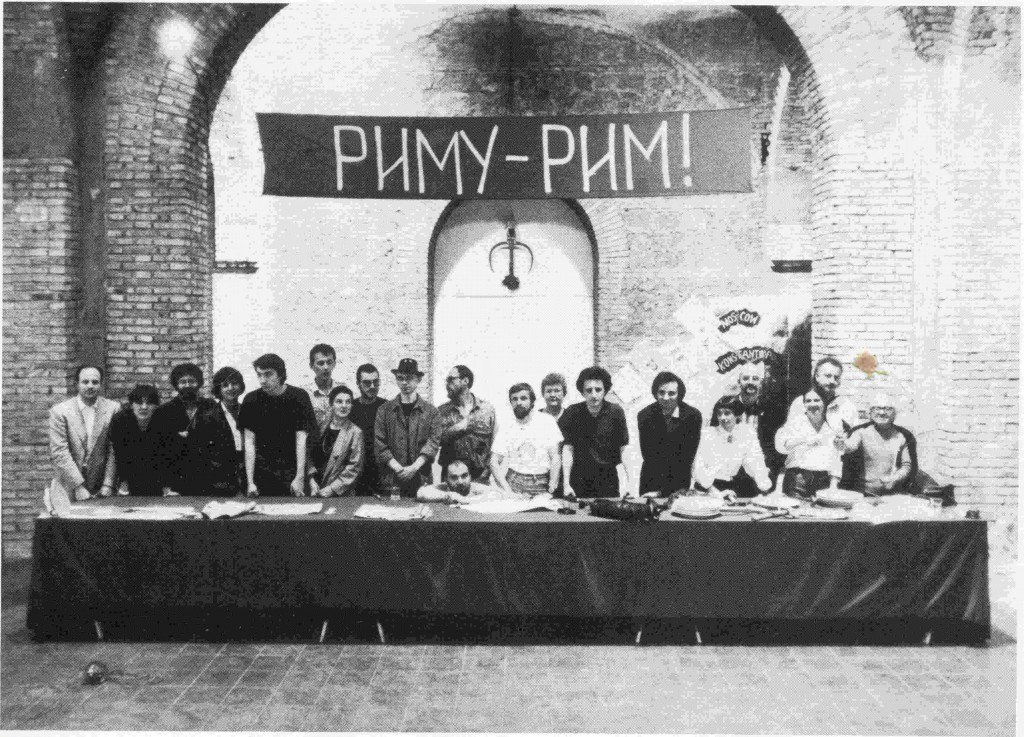

[17] Cf. Mosca: Terza Roma, Roma, Edizioni Sala 1, 1989, catalogue of the exhibition held in Sala 1, May-July 1989, without pagination. Viktor Misiano talks about this in his introductory essay to Moscow: the third Rome.

[18] Cf. Absolute Painting (Absolutnaia Kartina), ad vocem in the Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism, op.cit.

[19] Cf. Per-Arne Bodin, op. cit. : «Дитя в картине “Иван Грозный / Своего сына убивает” / Подходит близко, замирает / Пугается, хочет бежать, но поздно / Поздно» [The child in the painting Ivan the Terrible / kills his son/ gets closer, freezes / He is afraid, he wants to flee, but it is late / Late].

[20] Let us quote for example A banal reasoning about liberty: ” You have just finished washing up / and you see some more dishes to wash up / What sort of liberty is this / Living here until you are old, / Indeed you can stop washing up / But here come people / and they say: there are dirty dishes / Where is liberty here” . See also the Italian translation (D.A. Prigov, Banale ragionamento sul tema della libertà, trad. di P. Galvagni, http://rivistapaginazero.files.wordpress.com/2008/02/dmitrij-a-prigov.pdf. )

[21] On Dmitri Prigov’s Russian site, www.prigov.ru/images/inst.php, which was closed soon after his death on July 16th 2007, it was possible to find the reproduction of a long series of installation projects with the title: Фантомы инсталляций /Fantomy installjacij (Phantom installations).

[22] Ibidem.

[23] Ibidem

[24] Survival Zones, Prigov’s online lecture, 26th April 2007 at the Literary café “Bilingua”, http://www.prigov.org/interview/58/ . Cf. Also the interviews in: Dmitriy Prigov – Sergey Shapoval, Portretnaia galereia D.A.P., Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie (NLO), Moscow. 2003 and in: Sergey Shapoval (2012), op.cit.; and also the 1996 interview with Philip Metres, op. cit.

[25] Ksenya Gurshtein, op.cit..: Sideways Hitler “Prigov’s contribution to the lexicon of Moscow Conceptualism”. Cf: Urban dictionary: http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Sideways%20Hitler, “Sideways Hitler“.

[26] Ekaterina Degot, Dmitri Prigov and the Meat of Space, in op. cit., 50 sgg.

[27] Dimitri Ozerkov, Where is Prigov?, in D.A.P. Dmitri Prigov (St. Petersburg: Tabula Rasa, 2012): 78 sgg.

[28] Cf. TEDDY BEAR, ad vocem, in Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism, op.cit.

[29] Voina: artists at war, Danila Rozanov 17th February 2011,

http://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/danila-rozanov/voina-artists-at-war

[30] Пригов Дмитрий Александрович, Вознесение, http://prigov.ru/

[31] Survival Zones, Prigov’s online lecture of 26th April 2007, cit.

Nota integrale (ridotta per la Conferenza)

[1] Boris Groys, Moscow Romantic Conceptualism, “A-YA”, n.1, 1979, Parigi.

Durante la sua permanenza in Unione Sovietica. Groys ebbe modo di partecipare alle scene culturali – non ufficiali – di Mosca e Leningrado, pubblicando su 37, Chasy e altre riviste samizdat. Nel 1979 pubblicò sul samizdat di Leningrado 37, il saggio “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism” termine con il quale si riferiva al Concettualismo russo. Nello stesso anno il suo saggio venne ripubblicato a Parigi sul periodico d’arte A-YA.

In questo saggio Groys connette ed inserisce l’Arte concettuale russa degli anni ’60 e ‘70 alla corrente principale del concettualismo e dell’arte concettuale europea ed americana. Nel saggio egli discute del lavoro di Lev Rubinstein, Ivan Chuikow, Francisco Infante e del gruppo d’arte Collective Actions (Kollektivnye deistviya) fondato nel 1976 da Andrei Monastyrski, Georgii Kizevalter e Nikita Alekseev (cui poi si unirono Nikolai Panitkov, Igor Makarevich, Elena Elagina, Sergei Romashko e Sabine Hänsgen).

Editori di A-YA erano Alexander Sidorov con lo pseudonimo di «Alexej Alexejev» a Mosca e Igor Shelkovsky a Parigi. A-YA era anche distribuito negli U.S. da Alexander Kosolapov a New York. La rivista consisteva di 60 pagine in formato A4.

A-YA fece scoprire al mondo l’arte Sovietica – praticamente sconosciuta al pubblico – e l’arte contemporanea russa: è da questa rivista che si sentirono per la prima volta i nome di Dmitri Prigov, Ilya Kabakov e di Eric Bulatov, insieme a molti altri.

Nikita Alekseev, citato nel saggio del ’79 di Boris Groys’ è colui che, a Parigi, dove si trovava con Viktor Misiano, nel 1988 segnalò a Mary Angela Schroth (che ringraziamo della testimonianza) e propose la mostra Mosca Terza Roma di quegli artisti, poi realizzata a Roma nella galleria Sala1 nel maggio 1989. Vi esponevano Andreij Filipov, Georgij Litichevskij, Boris Orlov, Dmitri Prigov, Andreij Roiter, Konstantin Zvezdociotov, Vadim Zacharov. Ho conosciuto Prigov, insieme a sua moglie Nadia, in quella occasione e l’ho poi riincontrato a Mosca nel 1990. Lo invito nel 2006 al Museo Laboratorio di Arte Contemporanea della Sapienza di Roma da me diretto. È la sua prima personale in Italia “Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black“, 2-23 maggio 2006, a cura di Simonetta Lux e Domenico Scudero (cfr. Archivio del Mlac_ Museo Laboratorio di Arte Contemporanea nella rivista on line “luxflux.net”: http://www.luxflux.net/mlac/?p=14852 ).

Epstein, Mikhail: After the Future: The Paradoxes of Postmodernism and Contemporary Russian Culture, Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1995.

Mikhail Epstein è l’altro grande teorico del Concettualismo moscovita, di cui citiamo uno dei suoi più ampi testi.

La critica internazionale vede le origini del Concettualismo russo o Moscovita all’inizio degli anni ’70 nella Sots-art di Komar e Melamid e ne parla come di un movimento “che cercò di sovvertire l’ideologia socialista usando le strategie dell’arte concettuale” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moscow_Conceptualists).

Mikhail Epstein spiega più a fondo perché il concettualismo sia particolarmente appropriato alla cultura e alla storia della Russia, ma anche in che modo si differenzi dal concettualismo occidentale. “In Occidente – egli nota, pensando a Joseph Kosuth- il concettualismo sostituisce una cosa con un’altra – un oggetto reale con la sua descrizione verbale. In Russia tuttavia l’oggetto da sostituire è semplicemente assente”. Epstein riporta il pensiero di Iljia Kabakov (che ci richiama analoga posizione di Dmitri Prigov): “Tale contiguità, – secondo Kabakov- vicinanza, contatto con il nulla, vuoto, fonda, ci sembra, la fondamentale peculiarità del “concettualismo Russo”.(…) È come qualcosa che è nell’aria, una cosa a sé, una costruzione fantastica connessa con il nulla, che ha le sue radici nel nulla…In questo senso allora possiamo dire che il nostro modo di pensare, fin dall’inizio in verità, si sarebbe potuto definire “concettualismo”.

Su questa peculiarità del concettualismo russo, vedi anche: Donatella Possamai, Che cos’è il postmodernismo russo?, Padova, Editore Il Poligrafo, 2000.

Donatella Possamai scrive ( voce Vladimir Georgevic Sorokin, Enciclopedia Italiana, VII Appendice, Treccani): “Sono questi gli anni, intorno alla metà del 1970, che vedono Sorokin unirsi a quel circolo di intellettuali e artisti dell’underground noti sotto l’etichetta di concettualismo moscovita, una delle espressioni di più ampio respiro del postmodernismo russo per durata e significato culturale che muove dalla decostruzione e decontestualizzazione dei topoi della cultura sovietica per giungere a significare il vuoto metafisico di qualsiasi realtà. S., insieme a L. Rubinštejn e D. Prigov, ne diventa uno tra i più famosi rappresentanti” . da: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/vladimir-georgevic-sorokin_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/.

Cfr anche Ksenya Gurshtein,The Eloquent Spaces of Silence: D.A. Prigov’s Visual Art , conferenza tenuta il 22 febbraio 2013(dattiloscritto), Convegno Utopia III: Contemporary Russian Art and

the Ruins of Utopia , Londra, Courtauld Institute, 22-23 febbraio 2013.

Note italiano

[1] Boris Groys, Moscow Romantic Conceptualism, “A-YA”, n.1, 1979, Parigi.

[2] Per-Arne Bodin, The poet Dmitry Prigov before and after the fall of the Soviet Union , testo postato il 10 ottobre 2011 in http://www.postcolonial-europe.eu/sv/studies/97-the-poet-dmitry-prigov-before-and-after-the-fall-of-the-soviet-union-per-arne-bodin-stockholm-university.html, p.4. Per-Arne Bodin trae la citazione da “Dmitrij Aleksandrovič Prigov”, N.Ž.M.D.: Literaturnoe kafe v Internete, http://www.tema.ru/rrr/litcafe/prigov/, 10-09-2010.

[3] Ekaterina Degot, A Play on Stage, in: D.A. Prigov, Citizens! Please Mind Youeselves!, Mosca, Moscow Museum of Modern Art Publishing Program, catalogo della mostra al Moscow Museum of Modern Art,13 maggio -15 giugno 2008, p. 14 sgg.

[4] Nel n. 4 di A-YA- “A-YA n°4 – 1982 PERFORMANCES IN MOSCOW”

[5] Ekaterina Degot, op. cit., p. 51.

[6] Ksenya Gurshtein,The Eloquent Spaces of Silence: D.A. Prigov’s Visual Art , conferenza tenuta il 22 febbraio 2013(dattiloscritto, p. 10) Convegno Utopia III: Contemporary Russian Art and

the Ruins of Utopia , Londra, Courtauld Institute, 22-23 febbraio 2013. Riporta in particolare la introduzione di Dmitri Prigov stesso al suo libro Tri grammatici del 2003.

[7] Philip Metres, The End(s) of Russian Poetry: An Interview with Dmitry Prigov, in: http://behindthelinespoetry.blogspot.it/2007/07/ends-of-russian-poetry-interview-with.html

[8] Andrei Monastyrsky, ad vocem: THE NEW SINCERETY [Novaia iskrennosti], in Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism: An Adaptation of Andrei Monastyrsky’s «Slovar´ terminov Moskovskoj, kontseptual´noi shkoly», a cura di Octavian Eșanu, http://www.conceptualism-moscow.org/page?id=198&lang=en

[9] Per-Arne Bodin, op.cit., p.1

[10] Cfr. http://prigov.ru/: Пригов Дмитрий Александрович, Вознесение (testo introduttivo di Dmitri Prigov). Cfr. anche nota 36

[11] Ylena Fedotova “madman”, 8 luglio 2011, http://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/yelena-fedotova/dmitri-prigov.

[12] Cfr. Sergey Shapoval, (2012), op. cit. p.90.

[13] Cfr. Sergey Shapoval (2012), op. cit., p.91. Inoltre: Helena Fedotova, op. cit.

[14] Per-Arne Bodin, op.cit., p.8.

[15] Riprodotto in D.A. Prigov, Citizens! Please Mind Youeselves!, op. cit., p. 217.

[16] Riprodotto in ibidem., p. 234).

[17] Riprodotto in ibidem., p. 253. Di questa opera «Svet vo t´me svetit» [The light shines in the darkness], tratta Per-Arne Bodin, op. cit.

[18] Riprodotto in ibidem, p. 216).

[19] Cfr. Intervista a Philip Metres, op. cit. (1996-2007)

[20] Riprodotto in ibidem pp. 150-157).

[21] Cfr. Mosca: Terza Roma, Roma, Edizioni Sala 1, 1989, catalogo della mostra che si tenne nella Sala 1, maggio-luglio 1989, senza pagina. Ne parla Viktor Misiano nel saggio introduttivo Moscow: the third Rome.

[22] Cfr. Absolute Painting (Absolutnaia Kartina), ad vocem in Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism, op.cit.

[23] Cfr. Per-Arne Bodin, op. cit. : «Дитя в картине «Иван Грозный / Своего сына убивает» / Подходит близко, замирает / Пугается, хочет бежать, но поздно / Поздно» [Il bimbo nel quadro Ivan il terribile / Uccide suo figlio / Si avvicina, resta sospeso / Ha paura, vuole scappare, ma è tardi / Tardi]

[24] Tra i tanti testi in tal senso, voglio ricordare, inoltre, Banale ragionamento sul tema della libertà: «Hai appena lavato i piatti/ Ne vedi già dei nuovi / Ma quale libertà/ Qui vivendo sino alla vecchiaia, / In verità, puoi anche non lavare / Ma ecco arrivano varie persone / Dicono: ci sono i piatti sporchi – / Ma dov’è qui la libertà» (D.A. Prigov, Banale ragionamento sul tema della libertà, trad. di P. Galvagni, http://rivistapaginazero.files.wordpress.com/2008/02/dmitrij-a-prigov.pdf. ).

[25] Nel sito in russo di Dmitri Prigov, www.prigov.ru/images/inst.php, chiuso subito dopo la sua morte il 16 luglio 2007, sono riprodotte una lunga serie dei progetti di installazione, introdotti da un testo dal titolo: Фантомы инсталляций (Phantom installations).

[26] Пригов Дмитрий Александрович, Фантомы инсталляций , ibidem.

[27] Пригов Дмитрий Александрович, Фантомы инсталляций , ibidem.

[28] Survival zones, conferenza online di Prigov, tenuta il 26 aprile 2007 nel Literary café “Bilingua”,

http://www.prigov.org/interview/58/ . Cfr inoltre le interviste in: Dmitriy Prigov – Sergey Shapoval , Portretnaya galereya D.A.P., Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie (NLO), Moscow. 2003 e in: Sergey Shapoval (2012), op.cit.; e la intervista nel 1996 con Philip Metres, op. cit.

[29] Ksenya Gurshtein, op.cit..:Sideways Hitler “un contributo di Prigoval lessico del concettualismo moscovita”. Cfr: nell’Urban dictionary: http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Sideways%20Hitler , alla voce Sideways Hitler.

[30] Ekaterina Degot, Dmitri Prigov and the Meat of Space, in op. cit., p.50 sgg.

[31] Dimitri Ozerkov, Where is Prigov?, in D.A.P. Dmitri Prigov, Tabula Rasa, Saint Petersburg, 2012 , p.78 sgg.

[32] Cfr TEDDY BEAR, ad vocem, in Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism, op.cit.

[33] Voina: artists at war, Danila Rozanov 17 February 2011,

http://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/danila-rozanov/voina-artists-at-war .

[34] Пригов Дмитрий Александрович, Вознесение, http://prigov.ru/

[35] Survival zones, conferenza online di Prigov del 26 aprile 2007, cit.

Dmitri Prigov: Ascension (to the twenty-second floor), or Post-Utopian Harmony of a World Falling Apart

Simonetta Lux, january 29th 2014

The essay will be given by Simonetta Lux at the 6th International Prigov Conference in St Petersburg on 16-18 May 2016 with a new title: Materialization/Ascension/De-materialization: Prigov Post-Utopian Encyclopedia for a Transitional Age.

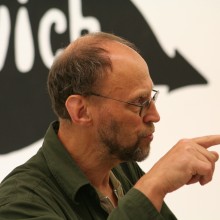

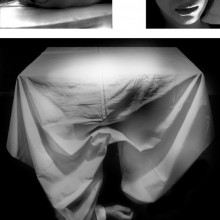

Exhibition Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black , at MLAC, Laboratory Museum of Contemporary Art, Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd-23rd of may 2006. Dmitri Prigov with Simonetta Lux, curator of the exhibition. Photo by Daniele Statera.

Exhibition Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black , at MLAC, Laboratory Museum of Contemporary Art, Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd-23rd of may 2006. Dmitri Prigov with Simonetta Lux, curator of the exhibition. Photo by Daniele Statera.

Dmitri Prigov has been recognized since 1979 as one of the masters of Russian literary Post-Modernism[1] from “a radically Post-Utopian position”. Today the work of more than forty years of activity is highlighted in a single body. He appears as a total artist and one of the most important theorists of the art of the transitional era in which he lived. Prigov always claimed not to be an artist who produces texts but one who produces artistic behaviour.[2] For this reason Prigov is an artistic unity. An art critic and curator Ekaterina Degot discovered an unpublished typed manuscript dated 1977, of a play by Prigov entitled A Play on Stage[3]. This work shows Prigov to be a poet artist, who from the beginning works with contemporary and international cultural awareness. The pièce brings together themes of the Theatre of the Absurd (Beckett), performative spatiality,[4] and the art of performance, which have been mainstream in art for the past fifteen years. Called the “playwright of Moscow Conceptualism,”[5] Prigov looks for a new relationship between audience and author. A Play on Stage includes certain elements and procedures that will be developed over time in the various forms his art will take. It is clear that Prigov and his friends in unofficial art have their eyes open to European and American art. The conceptual performative practice of Prigov mixes with a sense of the emptying of time and space, which he shares with nascent transnational Post-Modernism. It is for this reason that an art critic, philosopher, and curator Boris Groys applied the adjective Romantic specifically to Moscow Conceptualism. Prigov[6] continues to group together official arts that are traditionally separate (genres, styles, techniques) and the arts or icons of popular and mass communication.

It is therefore possible to speak of unity within his performative procedure and with a Post-Modernist emphasis. This gives continuity between the two worlds within which Prigov finds himself creating. In fact he lives the change from the imperative communicative process – that of the totalitarian Soviet regime – to the slippery communicative process brought about by the economic transformation of the USSR in a neo-liberal direction, despite their different values.

Prigov speaks of himself as a “project,” the D.A.P. project (the initials of his full name with patronymic, Dmitri Alexandrovich Prigov), which in Russian culture identified an official artist. He chooses the acronym, a fixed icon, to indicate an action and a new unofficial artistic figure. The choice of D.A.P. is already behaviour typical of the “Conceptual artist”.

How does the figure of the new artist operate? What role does Prigov give to art? What is the action of D.A.P. on the community within which he is formed? Can the art survive? How can it be measured against the great names of the past in art and literature?

Dmitri Prigov makes the most complex choice. He wants to consider the working of thought and position himself on the line that separates author from audience. From this borderline position he makes gestures and performs actions. He unites the two procedures: one, that of visual art, the other that of poetic and literary art. He makes writing and poetry an act of performance, while he makes visual, musical and dramatic art a conceptual plot. The real point is what he calls “the attempt to oppose the language inside language itself,” looking for its “non-totalitarian” possibility, as he writes in the interview given to Philip Metres in 1996 and published by the latter in 2007[7].

In this interview, Prigov defines as “totalitarian” any cultural discourse or narrative that is born within the consciousness of a certain epoch or within a clearly defined axiomatic system. This discourse is totalitarian in that it determines a state of subjection and loss of identity in the citizen or in the consumer (whom he calls the customer), or in the user to whom it is addressed (or imposed upon) and who never had, or no longer has, the tools for critical decoding. Prigov therefore carries out a real deconstruction process on every language (literary, poetic, political or visual) or discourse, a term used with reference to the French Post-Structuralist philosophers. He deconstructs the actual idea of the artist or the poet presenting it as a type: he or she is the phenomenon of a behavioural strategy and not a producer of texts. When he thinks of totalitarian communicative processes, he thinks not only of Soviet communicative Discourse but also of the neo-liberal and consumerist discourse dominant in the mass media. He also refers to all those stereotypical critical and literary traditions transmitted from one context to another through time. Such stereotypes determine a receptive automatism and a complete cognitive indifference. He is the first to observe himself in this condition, both in the period of the Communist regime and in the neo-liberalist regime in power from 1991. With his idea of a New Sincerity[8], which he had been thinking about since the 1970s, Prigov breaks the mirror from which the now emptied forms of languages and images of art emerge. His initially sneering irony softens.

The poetic action of Prigov is, according to Per-Arne Bodin, represented by one of his first lyrics, “I”, in which the poet imagines himself in a queue in the street (a daily situation in Communist Russia) and imagines inserting into it the greatest poets of the acclaimed Russian literary tradition, assigning to them the creative theme of “happiness forever”, with the chant of the Soviet pioneers in the background:

Вот в очереди тихонько стою

И думаю себе отчасти

Вот Пушкина бы в очередь

И Лермонтова в очередь

И Блока тоже в очередь

О чем писали бы? – О счастье!

Here I am quietly standing in line

And in part I think

Now, if you put Pushkin in line

And Lermontov in line

And Blok in line

What would they write about? About happiness!

By placing the classics of Russian literature in those queues so typical of the impoverished but well-organized Soviet reality, he declares them to be empty simulacra.

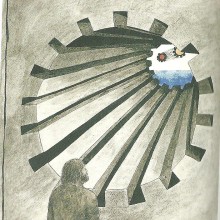

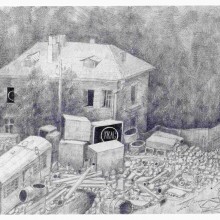

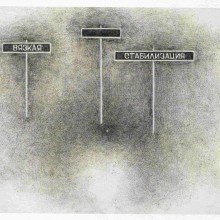

Prigov, like all the Moscow Conceptualists, wrote texts transformed into artifacts but as Ekaterina Degot has noted[9], their theatrical character, his practice of staging structures, singles him out. We can in effect imagine the poem quoted above acted on the stage, or read in one of the apartments of his artist friends, as happened from the middle of the 1970s, or performed in the street like many other actions. This staging structure exists in the first ink or gouache drawings like Aperture (c.1973) (Fig. 1), in drawings like Horror (1978-79) (Fig.2), the series Compositions with Labels(1990s) (Fig. 3) or even more clearly, in the great series of studies for installations (up to 2006) (Fig. 4) of the performance project Ascension[10], which he should have completed in 2007 with the Voina Collective, enfants terribles[11] of the new generation.

As D.A.P., Prigov started, at the beginning of the 1970s, to put himself forward as one who invades the world of words and as someone who decides how many tens of poems he must write in a month. The public were confronted by a quantitative and mechanical project,“a global machine-based project,” as Prigov referred to his poetic action stripped of content, form or style. He was accused of being an “insane graphomaniac” and an “insane computer”[12]. The artist suffered the last fires of repression with internment in a psychiatric institution in 1986, following the launch of the apparently mad Appeals to the Citizens”[13]. In fact he exhibits, in the form of Appeals, quotations from the New Testament, hanging them on street lights and at bus stops. It is one of the last episodes of police control over the artists of the Moscow underground culture. Prigov, like other unofficial artists, responded to the rejection of publication by producing Samizdat literature and – more seriously in the eyes of those in control– with irrational writings and actions, with the articulated processes of deconstruction of the Discourses. Space does not permit an analysis of the Prigovian deconstruction process, especially in view of the enormous number of texts left to us (more than 15,000). It is important to underline, however, that Prigov reworks stereotyped ways of writing (bureaucracy, syntax, grammar) using the weapon of irony and the play of absurd associations. He also utilises the vast resources of reproductions of images, from both art and advertising, or the emptied memory of the great ancient and contemporary artists, who are only named or reproduced and painted over. His deconstructions of bureaucratic ritualised political Discourse are completely conceptual. He makes the announcement concerning his change of address in the form of a typical obituary:

Центральный Комитет КПСС, Верховный Совет СССР, Советское правительство с глубоким прискорбием сообщают, что 30 июня 1980 года в городе Москва на 40-ом году жизни проживает.[14]

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and the Soviet government, with great pain announced that on 30th June 1980 at the age of 40, Dmitry Alexandrovich Prigov was a resident in Moscow.

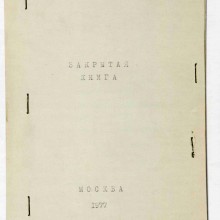

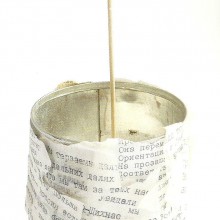

Thus, the text will become – whether or not the obituary is posted in the streets – an artistic action. Prigov transforms his own texts. Particularly striking are his Zakrytye Knigi (Closed Books), like that of 1977, sealed with metal pins (Fig. 5). Also important are the pages of the Zashtrikhovannye Stikhi (Shaded Verses) series of the 1970 (Fig. 6), These are poetic texts on which there are shadings in biro. The sheets of the series Stikhogrammy (Carmen Figuratum / Calligramme) are from the 1970s and 1980s (Fig.7) [15]. The artist has decided to transfer strictly poetic or literary works to a more complex world of action. This enables him to carry out a non-ideological action and to activate a non-conformist perception. He seals, shades and constructs, typing mechanically and he entombs his texts.

Prigov also described the conceptual transformation of writing and the word into object[16]. He produces, from the beginning of the 1970s until the first years of the new millenium, the objects of the Banki (Tins or Cans) series. The tins are renamed, with verbal or textual materials combined with or glued to them. This is conceptual work of a semantic nature, which intertwines the object with the name of the object, with another name/word and its object or action (following the Disegno geometrico by Giulio Paolini of 1960 and the well-known conceptual work by Joseph Kosuth of 1965, One and Three Chairs). The writing Banka gazety emerges from what becomes a “Tin of Papers,” a tin made of newspapers (Fig.8), and the writing Banka otrinutykh stikhov emerges from what becomes a Tin of discarded or rejected poetry (Fig. 9). Discarded, rejected texts, why? Prigov is carrying out a work of deformation and mixing, of deconstruction and combinatory reconstruction. He aims to show up the way partial and specialist Discourses work.

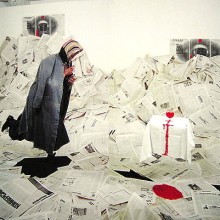

In the famous series of Gazety (Newspapers), Russian newspapers like Pravda are drawn and painted over with words such as “Pravda”(Truth), “Glasnost,” and “Khozraschet” (Cost Accounting) (Fig. 10). They are individual works but they also become installations (Fig. 10a) , for instance Glasnost produced in Cologne in 1989 (Fig. 11), or Krasnyi ugolok (The red/beautiful corner), realized in Rome in May 1989 (Fig. 12), a few months before the Fall of the Wall in Berlin[17].

In Azbuki(Alphabets) Prigov deconstructs and reconstructs. He mingles emotion and new sincerity with the vision of a painting, one of those absolutnye kartiny (absolute paintings)[18] which are a kind of powerful accumulator shaping the collective unconscious. In the poem describing a child looking at Il’ja Repin’s famous painting Ivan Groznyj ubivaet svoego syna (Ivan the Terrible kills his son)[19], the child is absolutely terrified, as if he was going to fall into the painting and so into the arms of the murderous tsar.

The series of installations with praying cleaning ladies (Fig. 13) can be explained in the light of the new sincerity. This is also the case with Prigov’s poetic texts[20], where he talks about every-day housework as a means to achieve divine energy:

Я с домашней борюсь энтропией

Как источник энергии божественной

Незаметные силы слепые

Побеждаю в борьбе неторжественной

В день посуду помою я трижды

Пол помою-протру повсеместно

Мира смысл и структуру я зиждю

На пустом вот казалось бы месте

I struggle with domestic entropy

As the source of divine energy

I conquer imperceptible blind forces

In an untriumphant struggle

I wash dishes three times a day

I wash and polish the floor all over

I erect the meaning and structure of the world

On a spot that would seem to be empty

In the installations he calls phantom projects [21], Prigov imagines an audience of voyeurs made up of individuals including himself , These installation projects are conceived as depositories of signs and traces of events he also experienced. In the face of these recurring staged signs, everyone becomes an actor of a movement of the mind. The whole body of these installation projects, which were extremely numerous starting from the 1990s, is a field of memory which recombines signs and events of what we could call the “first world” experienced by the artist (a crane jib, never ending repair maintenance, veils that hide the unknown) (Fig. 14-18). The spatial structure of these projects is always that of an empty cubicle, such as a hospital ward or a room in one of the new residential homes built by Khrushchev in a backward modernist style, just like Prigov’s home in the Moscow neighbourhood of Belyayevo. They are ghosts created on a sheet of paper, he says, something that on the whole constitutes “a perfect celestial world”, a heavenly world inhabited by angelic bodies, a virtual country with its ‘pure’ inhabitants. “Anyone can realise”[22] an installation of the interior of one’s home.

“Various objects and inhabitants of the world”, writes Prigov in the quoted text “pass through these models of installation. They are ghosts, changing in their various scales and combinations, but having three invariable base colours: three metaphysical colours, in fact, the main colours of Russian icons and the Russian avant-garde of the beginning of the century – black, white and red. Black – the colour of shelter, metaphysical and impenetrable mystery. White – the colour of energy … Red – the colour of life.”[23]. Among these projects, we think of the series dedicated to famous artists (This is Leonardo, This is Malevich, This is Matisse), whose evocation is a mere word. “For me as for any other individual, Pushkin is as good as a renowned porn actress, and a classical author is as good as a rock singer”, Prigov repeated this several times and also in his last interview of April 2007[24]. For this reason Prigov has produced himself in a variety of hetero-personifications (rock singer, actor, composer, writer, playwright, performer). He pretends to associate with the ordinary mass consumer for whom Leonardo da Vinci or Chekhov, a rock star or an opera singer, a sculpture by Michelangelo or a teddy bear are equivalent icons. In this way Prigov deconstructs the components of the Post-Modern cultural condition. He does this “through a sideways Hitler”(provesti bokovym Gitlerom)[25] surreptitiously introducing into the consciousness of the other something that otherwise could not directly penetrate into it. It is the sense of a spiritual and unknowable Beyond, the Beyond which Ekaterina Degot calls the meat of space[26] or magma. It is the glimpsed and unfathomable Black Magma Ozerkov speaks of [27]. It is identified in the phantom spaces and generates an obsessive sense of Horror.

Prigov stages icons or objects that make up the structures of the consciousness of reality: objects of mass consumption (the teddy bear, for example)[28] (Fig. 19), reproductions of art or the names of art, work tools including those associated with events, a few typical colours, the staging of the most common activities of everyday life (such as installations with supplicant cleaners with a bucket and scrubbing brush or installations of plumbing works).

The process of deconstructing the Discourses is attenuated by means of a different tension that is grasped by new generations. One of the collectives of artists most scathing and disrespectful of never-changing power is called Voina (War)[29] and it identified in Prigov a master of non-ideological cultural activism towards art (Fig. 20-21).

The young students/artists of the group seem to recognise the real meaning of Prigov’s work: the mystical isolation and the everyday solitude of the Post-Utopian artist. They were planning to stage Prigov’s last project which was published on his website with the title Ascension[30]. Voina were meant to transport the poet Prigov up to the twenty-second floor of a building, sitting in a wardrobe reading his poems whilst dressed in a military coat. Prigov speaks in his text of the wardrobe as a shell, a shelter for a man “who has withdrawn from the world into a basement, an underground artist” practising a secret asceticism, a “work of the soul and the spirit hidden from prying eyes. Just like Saint Girolamo, in a grotto, where finally there is a shaft of divine light which carries him to Heaven and saves him,” Dmitri Prigov is probably thinking of the San Girolamo penitente by Leonardo da Vinci (c.1480) in the Vatican Gallery in Rome.

“Thus, finally, the ascension to the twenty-second floor has arrived for the man sitting in the wardrobe, for all the suffering and torment experienced by the world and as reward for its unproclaimed spiritual undertakings”.

Ascension is Prigov’s last performance project, unfinished because of his death. Incomplete like the Saint Girolamo by Leonardo da Vinci. It is a project which in no respect excites pity, as is the case with all Prigov’s work. It is, rather, in harmony with what Prigov said in the online lecture Survival Zones of April 2007. He said that he hoped for man and art: the reconquest of dignity and the survival of art.[31]

In the last verses of Ascension, addressed to the students, he writes of himself: “Obviously, the superior powers could not entrust the task of the Ascension to simple workers who lift and move physical and bodily loads different heights and distances. It would have been for them a work of mere physical routine, whether poorly or well paid. No, the superior powers need non-professional hands, for which, in turn, this would be a commitment and a job not of muscles but of the soul and the spirit. Dmitry Prigov.”

Translated by Jeremy Barnard

Foto di gruppo per la mostra Mosca terza Roma, 1989, Roma Galleria Sala 1, da sinistra: Alfredo Bardinetti, Anara, Massimiliano Ruta, Daniela De Dominicis, Vadim Zacharov, Georgij Litichevskij, Olia Roiter, Andreij Roiter, Kostantin Zvezdociotov, Dimitrij Prigov, Andreij Filippov, Boris Orlov, Nadija Prigov, Viktor Misiano, Elvio de Sanctis, Silvia Stucky, Jacopo Benci, Mary Angela, Schroth, Fabio Caruso, Tito Amodei.

Восхождение

Ascensione (al 22mo piano)di Dmitri Prigov:armonia postutopica in un’epoca di transizion

Simonetta Lux, 29 gennaio 2014

Il saggio sarà dato da Simonetta Lux come conferenza al 6° Convegno Internazionale “Prigov”, a San Pietroburgo dal 16 al 18 maggio 2016 con il nuovo titolo: Materializzazione/Ascensione/Dematerializzazione in Dmitri Prigov. Enciclopedia Postutopica per un’Epoca di Transizione.

Dmitri Prigov è stato riconosciuto dal 1979 come uno dei maestri del post modernismo letterario russo[1] dalla posizione “radicalmente post utopica”.

Oggi l’opera di oltre quaranta anni di attività viene illuminata come un corpo unitario. Egli appare come artista totale e teorico dell’arte tra i più importanti dell’epoca di transizione che ha vissuto. Prigov ha sempre affermato di non essere uno che produce testi, ma uno che produce comportamento artistico: perciò Prigov è tutta un’unità di arte.

“Я же не произвожу текст, я произвожу художественное поведение“[2].

Ekaterina Degot ha scoperto un inedito dattiloscritto drammaturgico di Prigov dal titolo: A Play on Stage datato 1977[3]. Con questa opera Prigov appare un artista poeta, che opera fin dai suoi inizi nella consapevolezza culturale contemporanea e internazionale. La pièce riunisce in sé temi del teatro dell’assurdo (Beckett), della spazialità performativa [4] e dell’arte della performance (da un quindicennio mainstream dell’arte). Detto “drammaturgo del concettualismo moscovita”[5] , Prigov cerca una relazione nuova tra pubblico e autore. A Play on Stage comprende elementi e procedure che si svilupperanno nel tempo nelle diverse materie in cui la sua arte si incarna. E’ chiaro che Prigov e i suoi amici dell’arte non-ufficiale hanno gli occhi aperti sull’arte europea ed americana. La pratica performativa concettuale di Prigov, si combina con un senso di svuotamento spazio temporale, che condivide col nascente postmodernismo transnazionale. Per questo Boris Groys ha coniato per lo specifico Concettualismo Moscovita, l’aggettivo Romantic. Prigov [6] continuerà a porre sullo stesso piano le arti ufficiali tradizionalmente separate (generi, stili, tecniche) e le arti o icone della comunicazione popolare e di massa.

Per questo si può parlare di unità della sua procedura performativa concettuale con accento post modernista. Ciò dà una continuità tra i due mondi in cui Prigov si è trovato a creare. Dmitri Prigov vive infatti il passaggio dall’imperativo processo comunicativo – proprio del regime totalitario sovietico – al subdolo processo comunicativo consumistico determinato dalla trasformazione economica dell’URSS in senso neoliberista. Seppure con un valore diverso.

Egli parla di se stesso come di un ‘progetto’, il progetto D.A.P. (la sigla del suo nome completo di patronimico Dmitri Alexandrovic Prigov) che nella cultura russa identificava un artista ufficiale. Sceglie l’acronimo, una fissa icona, per indicare un’azione e una nuova figura di artista non ufficiale. La scelta D.A.P. è già un ‘comportamento’ da ‘artista concettuale’.

Come opera questa nuova figura di artista? Che ruolo dà Prigov all’arte? Qual è l’azione del D.A.P. sulla comunità in cui egli si forma, vive e realizza? Può sopravvivere l’arte? Come si misura con i grandi nomi dell’arte e della letteratura del passato?

Dmitri Prigov sceglie la cosa più complessa: vuole considerare il funzionamento del pensiero e collocarsi nella linea che separa l’autore dal pubblico. Da tale linea di confine, lancia gesti e azioni. Unifica in una sola le due procedure: una, quella dell’arte visuale; due, quella dell’arte poetica e letteraria. Fa della scrittura e della poesia un atto di performance e fa dell’arte visuale, musicale e drammaturgica, una trama concettuale. La questione è quella che lui chiama “il tentativo di contrastare il linguaggio all’interno del linguaggio stesso”, cercandone la possibilità “non totalitaria”, come scrive nell’intervista data nel 1996 a Philip Metres e da questi pubblicata nel 2007 [7].

Prigov, nell’intervista, definisce “totalitario” ogni discorso o narrativa culturale che nasce all’interno di una coscienza epocale o all’interno di una assiomatica ben definite. Esso è totalitario in quanto determina uno stato di soggezione e sostanzialmente di perdita di identità nel citizen o nel consumatore (che lui chiama customer) o nel fruitore cui viene rivolta o imposta. A costoro – egli presume- non sono dati, o non hanno più, gli strumenti di decodifica critica.

Perciò Prigov compie un vero e proprio processo di decostruzione su ogni linguaggio (letterario, poetico, politico, o visuale) o discorso. Questo termine è usato in riferimento ai filosofi post strutturalisti francesi. Egli decostruisce in primo luogo l’idea stessa dell’artista o del poeta, presentandolo come un tipo: egli è il fenomeno di una strategia di condotta e non un produttore di testi. Quando egli pensa ai processi comunicativi totalitari, pensa non solo al Discorso comunicativo Sovietico, ma anche al Discorso neoliberale e consumistico dominante nei mass media. Si riferisce anche a tutte quelle tradizioni critiche e letterarie stereotipate che sono trasmesse da un contesto ad un altro, attraverso il tempo: tali stereotipi culturali determinano un automatismo della recezione ed una vera e propria indifferenza conoscitiva. Lui è il primo ad osservare se stesso in questa condizione, sia ai tempi del regime comunista, sia nel tempo del regime neoliberista vigente dal 1991. Con la sua idea di una New Sincerity[8] cui pensa sin dagli anni ’70, Prigov rompe lo specchio da cui emergono le figure ormai svuotate di linguaggi e immagini dell’arte. La sua ironia prima ghignante si addolcisce.

La azione poetica di Prigov è, secondo Per-Arne Bodin,[9] rappresentata da una delle sue prime liriche: “I” (Io), nella quale il poeta si immagina in fila, per strada (una situazione quotidiana nella Russia comunista) e immagina di inserirvi i più grandi poeti della conclamata tradizione letteraria russa, attribuendo loro – se fossero lì, il tema creativo della felicità per sempre, come se fosse sullo sfondo il canto dei pionieri sovietici:

Вот в очереди тихонько стою

И думаю себе отчасти

Вот Пушкина бы в очередь

И Лермонтова в очередь

И Блока тоже в очередь

О чем писали бы? – О счастье!

Ponendo i grandi classici della letteratura russa in quelle file tipiche della realtà sovietica impoverita ma ben organizzata, egli ne enuncia il tratto di simulacri ormai vuoti.

Prigov – come tutti i concettuali moscoviti- ha scritto testi trasformandoli anche in artefatti (artifacts): tuttavia, ha fatto notare Ekaterina Degot, il carattere teatrale – cioè la pratica delle staging structures, lo differenzia. Possiamo in effetti immaginare la poesia sopra citata agita su un palcoscenico, o letta in uno degli appartamenti degli amici artisti, come avveniva sin dalla metà degli anni ’70 oppure messa in scena per strada come tante altre azioni o performance. D’altronde questo carattere di staging structure c’è, è vero, sia nei primi disegni a inchiostro e gouache come Aperture (ca. 1973) sia in disegni come Horror del 1978-79 o nella serie delle Composizioni con cartelli degli anni ’90 e infine, più chiaramente, nella grande serie di studi per installazioni fino al 2006, per concludersi con il progetto di performance Ascensione[10] che avrebbe dovuto realizzare nel 2007 con il Collettivo Voina, enfants terribles [11] della nuova generazione.

La messa in opera drammaturgica caratterizza la sua opera sia di ambito visuale sia dell’ambito letterario, sin dai suoi inizi.

Come D.A.P., Prigov inizia negli anni ’70 a proporsi come uno che invade il mondo di parole e come uno che decide quante decine di poemi deve scrivere in un mese.

Il pubblico colto si trovò di fronte a un progetto quantitativo e meccanico: “a global machine-based project” scrive Prigov a proposito della sua azione poetica disincarnata da contenuto, forma o stile.

E gli si risponde con l’accusa di “pazzo grafomane” “insane graphomaniac” e “pazzo computer” “insane computer”[12].

L’artista subisce gli ultimi fuochi della repressione con una reclusione in manicomio, nel 1986, in seguito al lancio di apparentemente folli Appelli ai cittadini[13]: egli in effetti espone ai lampioni e alle fermate d’autobus citazioni dal Nuovo Testamento in forma di Appelli. E’ uno degli ultimi episodi della prassi di controllo della polizia sugli artisti della cultura underground moscovita. Prigov come gli altri artisti non ufficiali rispondeva al rifiuto di pubblicazione con i samizdat e – cosa più grave agli occhi dei controllori – con scritture e azioni irrazionali, insomma con articolati processi di decostruzione dei Discorsi.

Non è qui il caso di approfondire la questione del processo decostruttivo prigoviano, anche in considerazione del gran numero di testi lasciatici (da 15000 in su).

Si deve sottolineare soprattutto che Prigov opera su modi di scrittura stereotipi (burocrazia, sintassi, grammatica) con l’arma dell’ironia e con il gioco delle associazioni assurde. Egli opera anche sul vasto patrimonio delle riproduzioni di immagini, artistiche o pubblicitarie, o sulla memoria svuotata dei grandi artisti antichi o contemporanei, che vengono solo nominati oppure riprodotti e ridipinti sopra.

Sono del tutto concettuali le sue decostruzioni del Discorso burocratico o politico ritualizzato. Scrive nella forma del tipico necrologio, l’avviso relativo al suo cambio di indirizzo:

Центральный Комитет КПСС, Верховный Совет СССР, Советское правительство с глубоким прискорбием сообщают, что 30 июня 1980 года в городе Москва на 40-ом году жизни проживает. [14]

Questo è sì un testo (text), tuttavia lo pseudo-necrologio sarà appeso per strada o potrà esserlo, diverrà azione artistica. Prigov trasforma i suoi stessi testi. Ci colpiscono i suoi Закрытые Книги /”Zakrytyye Knigi”, [Libri chiusi]. come quello del 1977, sigillato da punti metallici [15]. Sono significativi i fogli della serie Заштрихованные Стихи /”Zashtrikhovannyye Stikhi”, [Poesia ombreggiata] sempre degli anni ’70 [16]: essi sono testi poetici su cui si sovrappongono ombreggiature a penna biro. Sono degli anni ’70-’80 [17] i fogli della serie Стихогаммы (Stikhogammy )[Stichogramma/ Carmen Figuratum / Calligramme][18]. L’artista ha deciso di trasferire lavori strettamente poetico-letterari, in un mondo di azione più complesso. Ciò gli consente di compiere una azione non ideologica e di attivare una percezione non conformistica. Sigilla, ombreggia, costruisce con meccanica battitura, tomba i suoi testi.

Prigov ha poi anche descritto la trasformazione concettuale della scrittura o della parola in oggetto[19] . Realizza dagli inizi degli anni ’70 fino agli anni 2000 gli oggetti della serie Banki [Barattoli] o [Lattine] (ОБЪЕКТЫ ИЗ СЕРИИ “БАНКИ”/ Ob”yekty iz serii ” Banki ” ). Le lattine sono rinominate con i materiali verbali o testuali combinati o incollati ad esse. Si tratta di un’opera concettuale a carattere semantico: intreccia l’oggetto e il nome dell’oggetto, con un altro nome/parola e il suo oggetto o azione ( sulla scia del Disegno geometrico di Giulio Paolini del 1960 e della notissima opera concettuale di Joseph Kosuth del 1965 One and Three Chairs). La scritta ГАЗЕТА БАНКA Gazeta banka) emerge da quello che – fatto con giornali- diventa “Barattolo di giornali”: la scritta БАНКA ОТРИНУТЫХ СТИХOB (Banka otrinutykh stikhob) [20] emerge da quello che diventa un Barattolo di poesia scartata o rifiutata. Testi rifiutati e/o scartati: perché?

Prigov sta compiendo un lavoro di deformazione e contaminazione, di decostruzione o ricostruzione combinatoria: tende a far esplodere il funzionamento dei Discorsi parziali e specialistici di cui i giovani oggi sono preda, come di una Verità. Nella nota serie dei Newspapers (“ГАЗЕТЫ”), i giornali quotidiani russi, come la “Pravda”, vengono disegnati e dipinti sopra con scritte di parole all’ordine del giorno”:”Pravda”, “Glasnost´. Sono dipinti, ma diventano anche installazioni: come quella realizzata a Colonia nel 1989 “Glasnost”. O quella dello stesso anno, realizzata in maggio poco prima della caduta del Muro di Berlino a Roma “Angolo rosso/bello” (Krasnyj ugolok) [21]. Decostruisce e ricostruisce, negli Abzuki [‘ABC’, ‘abbecedari’, ‘alfabeti/glossari dall’A alla Z’]. Contamina con emozione e con new sincerity la visione di un quadro, uno di quegli absolutnaia kartina, potenti accumulatori/formatori dell’inconscio collettivo[22]: nel poema che descrive il bambino di fronte alla famosa pittura di Il´ja Repin Ivan Groznyj svoego syna ubivaet [Ivan il terribile uccide suo figlio][23]. Il bambino è descritto da Prigov così terrorizzato come se stesse per cadere dentro il quadro, tra le braccia dello zar assassino.

Con la new sincerity possiamo spiegare sia la serie dei progetti di installazione con donne delle pulizie oranti (ЭСКИЭ ИНСТАЛЛЯЦИИ С ФИГУРОИ УБОРЩИЦЫ ), sia nei suoi testi poetici[24] in cui parla del lavoro quotidiano casalingo come mezzo per raggiungere la divina energia.

Я с домашней борюсь энтропией

Как источник энергии божественной

Незаметные силы слепые

Побеждаю в борьбе неторжественной

В день посуду помою я трижды

Пол помою-протру повсеместно

Мира смысл и структуру я зиждю

На пустом вот казалось бы месте

Nei progetti di installazione che chiama phantom installations [25], Prigov immagina un pubblico di voyeurs fatto di individui qualunque, compreso se stesso. I progetti di installazione sono concepiti come depositi di segni o di tracce di eventi vissuti anche da lui.

Di fronte agli essenziali segni messi in scena nella installazione, ognuno diventa attore di un movimento della mente.

L’insieme dei suoi progetti di installazione, numerosissimi a partire dagli anni ’90, sono dunque campo della memoria: vi si ricompongono segni od eventi di quello che abbiamo chiamato ‘primo mondo’ vissuto dall’artista. (il braccio della gru, le tubature di riparazioni infinite, i veli che nascondono l’ignoto).

La struttura spaziale dei progetti è sempre quella di un box vuoto, come cella di ospedale o come stanza delle nuove abitazioni residenziali realizzate da Krushev in stile modernista attardato. Proprio come la sua casa nel quartiere moscovita di Belyayevo.

Sono fantasmi creati su un foglio di carta – scrive Prigov – qualcosa che nell’insieme costituisce “un perfetto mondo celeste”, un mondo paradisiaco dove abitano corpi angelici, un paese virtuale con i suoi abitanti ‘puri’. Un’installazione, “chiunque può realizzarla”[26], dell’interno delle proprie case. “Vari oggetti che abitano il mondo” scrive ancora Prigov nel testo citato, “attraversano questi modelli di installazione, fantasmi mutevoli in diverse scale e combinazioni, ma avendo tre colori base non variabili. Tre colori metafisici, infatti, colori principali delle icone russe e dell’avanguardia russa di inizio secolo – nero, bianco e rosso. Nero – il colore del rifugio, mistero metafisico e impenetrabile. Bianco – il colore dell’energia … Rosso – il colore della vita. (…)”.[27]

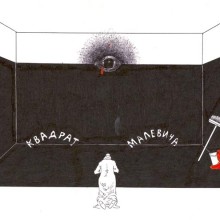

Tra questi progetti, pensiamo alla serie dedicata agli artisti famosi (This is Leonardo, This is Malevich, This is Matisse) la cui evocazione è solo un nome. “Tanto per me, quanto per tutti gli altri individui qualunque, Pushkin vale quanto una attrice porno di fama e un autore classico quanto un cantante rock”, ha scritto Prigov più volte e infine nell’ultima intervista nell’aprile 2007 [28].

Prigov per questo si era prodotto in svariate etero-personificazioni (cantante rock, attore cinematografico, compositore, sceneggiatore, drammaturgo, performer). Egli finge di accomunarsi a quel fruitore qualunque o massificato per il quale un Leonardo da Vinci o un Checov, un cantante Rock o un interprete di Opera, una scultura di Michelangelo o un orsetto di pelouche sono divenute icone equivalenti. In questo modo Prigov decostruisce le componenti della condizione culturale postmoderna. Le asseconda e “through a sideways Hitler” (provesti bokovym Gitlerum)[29] introduce surrettiziamente nella coscienza dell’altro qualcosa che altrimenti non potrebbe penetrarvi direttamente. Il senso di un Beyond spiritualistico e inconoscibile. E’ l’Oltre che la Degot chiama meat of space [30]o magma ; è il Nero magma intravisto e inaccessibile di cui parla Ozerkov[31] . Si individua nei phantom spaces e determina un ossessivo senso di Horror.

Prigov mette in scena icone o oggetti che compongono le strutture della coscienza del reale (oggetti di consumo popolare come il teddy bear [32], riproduzioni dell’arte o di nomi dell’arte; strumenti del lavoro, anche associati ad eventi; pochi tipici colori o la messa in scena delle più comuni azioni della quotidianità (ad esempio i progetti di installazione con le pulitrici oranti, con secchio e spazzolone; o i progetti di installazione con idraulico).

Il processo di decostruzione dei Discorsi si attenua, in una tensione diversa che viene colta dalle nuove generazioni. Uno dei collettivi di artisti più graffianti e irrispettosi del potere sempre uguale che si chiama Voina[33] (Guerra), ha identificato in Prigov un maestro di attivismo culturale non ideologico attraverso l’arte.

I giovani studenti/artisti del gruppo ci sembra riconoscano il senso ultimo dell’opera di Prigov- il mistico isolamento e la solitudine quotidiana dell’artista post-utopico. Programmano di mettere in scena l’ultimo progetto di Prigov che è pubblicato nel sito di Prigov col titolo Ascensione [34]. Voina avrebbe trasportato su fino al 22° piano di un edificio il poeta Prigov, persona famosa da tempo, mentre legge delle poesie stando seduto dentro un armadio, vestito di un soprabito militare. Prigov parla nel suo testo dell’armadio, come di un guscio, un riparo per un uomo “che si è ritirato dal mondo in un seminterrato, artista underground” praticante di un ascetismo segreto, “lavoro dell’anima e dello spirito a riparo da occhi indiscreti. Come lo stesso San Girolamo, in una grotta, dove, finalmente, spunta un fascio di luce divina, portandolo in cielo e salvandolo. (…)”: Dmitri Prigov pensa probabilmente al San Girolamo penitente di Leonardo da Vinci (1480 circa) della Pinacoteca Vaticana di Roma.

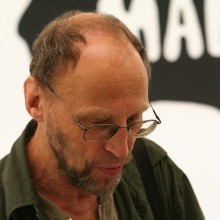

Exhibition Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black , at MLAC, Laboratory Museum of Contemporary Art, Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd-23rd of may 2006. Dmitri Prigov at work. Photo by Domenico Scudero, co-curator of the exhibition..

Exhibition Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black , at MLAC, Laboratory Museum of Contemporary Art, Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd-23rd of may 2006. Dmitri Prigov at work. Photo by Domenico Scudero, co-curator of the exhibition..

“Così, finalmente, è arrivata l’ascensione al 22° piano per l’uomo seduto nell’armadio, per tutte le sofferenze e tormenti ricevuti dal mondo, come ricompensa per le imprese spirituali non annunciate”.

Ascension è l’ultimo progetto di performance di Prigov, non realizzato a causa della sua morte. Incompiuto come la tavola del San Girolamo di Leonardo da Vinci.

E’ un progetto niente affatto patetico, come in tutto ciò che Prigov fa: è invece in sintonia con quanto Prigov diceva – nella conferenza online Survival zones dell’aprile 2007. Egli diceva di sperare per l’uomo e per l’arte: la riconquista della dignità e la sopravvivenza dell’arte. [35]

Negli ultimi versi di Ascensione egli scrive di sé, rivolto agli studenti: “Ovviamente, le forze superiori non potevano affidare questo incarico dell’Ascensione a semplici lavoratori da sollevamento e spostamento di pesi fisici e carnali a diverse altezze e distanze. Per loro sarebbe un lavoro fisico di routine, scarsamente o generosamente pagato. No, le forze superiori hanno bisogno di mani non professionali, per le quali, a loro volta, questa sarebbe impresa e lavoro, non dei muscoli, ma dell’anima e dello spirito. Dmitry Prigov”.

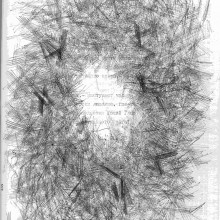

1.Aperture, 1974, paper, cardboard, gouache, ink, pen, 44×32,2 cm. (Name and date by author on back), by Degot

1.Aperture, 1974, paper, cardboard, gouache, ink, pen, 44×32,2 cm. (Name and date by author on back), by Degot

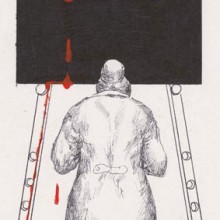

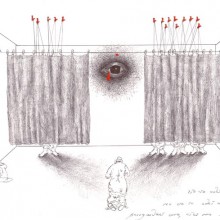

2.Horror, App. 1978-79 (dated by Orlov), paper, pencil

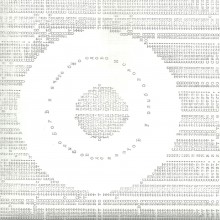

3.From “Compositions with Labels”, 1990s (30 papers in total), paper, ballpoint pen, 21×29,5cm (each), (Dated on the basis of analogous plates published in: Dmitri Alexandrovich Prigov, Written from 1990-1994, Moscow, Novoe Literaturnoe obozrenie, 1998), (Композиции с табличками: in http://www.prigov.org/kompozitiontable/

4. Photo projects – Dmitri Prigov selfportraits (tableau vivant): nested in his own home, under or inside table, cupboards, cabinets, forwarding his “Ascension” performance with VOINA Group da: www.prigov.ru/action/foto1.php

5. Closed Book, 1977, paper, typescript text, 19x13cm

6. Sheets from the series “Shaded Poetry”, 1970s, 11 sheets, paper, text, ballpoint pen, 29,5x21cm

7. Sheet from the series “Poetrygrams”, 1970-80s, paper, typescript, (Captions transited by David Riff) 29,5x21cm.

“Another theme that is not deconstructed in his poetry, or only partially deconstructed, is the Christian motif that runs through his all poetry. We noticed it already in the poem about household work. Another example is his early poemogram, “stichogramma”, “Svet vo t’me svetit”, “The light shines in the darkness”, with a passage from the Bible used in a text collage” cfr: Per-Arne Bodin, The poet Dmitry Prigov before and after the fall of the Soviet Union , testo postato/posted il 10 ottobre 2011 in http://www.postcolonial-europe.eu/sv/studies/97-the-poet-dmitry-prigov-before-and-after-the-fall-of-the-soviet-union-per-arne-bodin-stockholm-university.html

8. Word can (Objects from the Series “Cans”), tin can, plaster, wood, cardboard, paper with typed text, Height: 8,3 cm, diameter 7,5 cm

9. Can of Cuttings, (Objects from the Series “Cans”), tin can, plaster, wood, cardboard, paper with typed text, glue, newspaper cuttings, Height: 8 cm, diameter 7,5 cm

10 a. MENE, TEKEL, UPHARSIN, (installation), 1990, Frankfurt, Prigov’s newspapers drawings on the walls, acrylic painting, newspapers, variable dimensions.

10. ANGLE (Угол ), installation,1989, Köln, newspaper’s installation on the walls and on the floor, acrylic painting, variable dimensions

11. Snowy Space ( installation with scarecrow prayerful), 1991, Cologne, Prigov’s newspapers drawings on the walls, acrylic painting, newspapers, blood glass, scarecrow prayerful, variable dimensions.

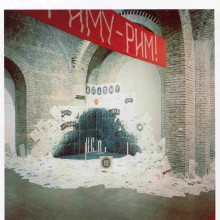

12. Angolo Rosso (Installation), Roma Galleria Sala 1, 1989, Prigov’s newspapers drawings on the walls, acrylic painting, newspapers, red banner (Roma – Roma!!/ РИМY – Рим!! inscription), variable dimensions.

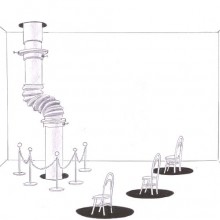

13. INSTALLATION sketch with Cleanig Lady (PROJECT/SKETCH), 1996? ,(dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects 1990-2000s), paper, acrylic, bellpoint pen, pencil, 20,8 x29,4 cm about

14. INSTALLATION sketch dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects (1990- 2000s),

15. Malevich Square, installation sketch, 1991, paper, ballpoint pen, pencil, 20x 30 cm, (dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects 1990-2000s)

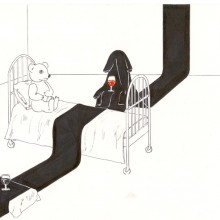

16. INSTALLATION sketch WITH BEAR (PROJECT/SKETCH), 2000 about, (dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects 1990-2000s), paper, acrylic, bellpoint pen, pencil, 20,8 x29,4 cm

17. INSTALLATION sketch dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects (1990- 2000s)

18. Installation sketch with Cleaning Lady, (no later than 1997), paper, ballpoint pen, pencil, 20×30 cm ((dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects 1990-2000s)

19. INSTALLATION sketch WITH BEAR (PROJECT/SKETCH), 1996- about ,(dalla Serie Phantom Installation Projects 1990-2000s), paper, acrylic, bellpoint pen, pencil, 20,8 x29,4 cm (date on back: this project was realized at the Guelman Gallery “life Line” 1996)

20-21 Photo projects – Dmitri Prigov’ selfportraits (tableau vivant): nested in his own home, under or inside table, cupboards, cabinets, forwarding his “Ascension” performance with VOINA Group

Exhibition Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black , at MLAC, Laboratory Museum of Contemporary Art, Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd-23rd of may 2006. Dmitri Prigov at work and with Simonetta Lux, curator of the exhibition, and others. Photo by Daniele Statera.

Exhibition Dmitri Prigov. On the Boundary of the Black , at MLAC, Laboratory Museum of Contemporary Art, Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd-23rd of may 2006. Dmitri Prigov at work and with Simonetta Lux, curator of the exhibition, and others. Photo by Daniele Statera.